How debt relief can support development efforts for more than 1 billion people

How do emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) mobilize the financing needed to meet the 2030 agenda and the Paris Agreement without compromising their debt sustainability or, indeed, their creditworthiness? A new report by the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project performs an in-depth analysis of global external debt sustainability (DSA) to estimate the extent to which EMDEs can mobilize the recommended levels of external financing without jeopardizing debt sustainability.

Investment in development and climate while maintaining economic and financial stability is a balance that emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) need to find in order to meet the United Nations' 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and the Paris Agreement.

EMDEs (with the exception of China) need a major investment boost to fulfill the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement. An Independent Expert Group of the Group of 20 (G20) estimates that EMDEs, with the exception of China, will need to mobilize 3 trillion dollars annually, 1 trillion from external sources and 2 trillion domestically, by 2030.

Mobilizing such massive investment volumes will be challenging, especially considering that many EMDEs are currently struggling with high debt burdens and high interest rates that can quickly compound debt vulnerabilities.

How do EMDEs mobilize the financing needed to meet the 2030 agenda and the Paris Agreement without compromising their debt sustainability or, indeed, their solvency?

The new report from the Debt Relief for a Green and Inclusive Recovery (DRGR) Project - a collaboration between Boston University's Center for Global Development Policy, the Heinrich Böll Foundation and the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS, University of London, performs an in-depth analysis of global external debt sustainability (DSA) to estimate the extent to which EMDEs can mobilize the recommended levels of external financing without jeopardizing debt sustainability.

We found that, of 66 economically vulnerable EMDEs that are considered low-income countries by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 47 EMDEs with a total population of more than 1.11 billion people will face insolvency problems in the next five years as they seek to build investments to meet climate and development goals. A further 19 EMDEs lack the liquidity and fiscal space to invest in climate and development and will not be able to finance the necessary investments without increased credit or liquidity support. These results indicate that debt relief needs to be provided if highly vulnerable EMDEs, and indeed the international community as a whole, are to stand a chance of delivering on the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement.

Stratospheric levels of indebtedness during a critical decade

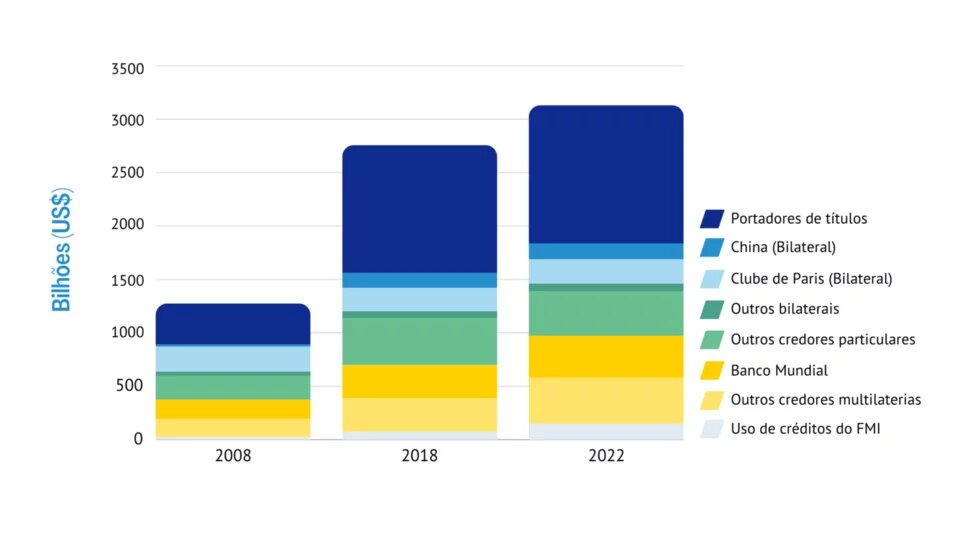

Public and publicly guaranteed (PPG) external debts have hit record levels while current debt servicing is at a height not seen since the 1990s, when much of the Global South was on the margins of default. For EMDEs (with the exception of China), external PPG debts have more than doubled since 2008, reaching 3.1 trillion dollars by 2022, as seen in Figure 1. In addition, debt service payments are at an all-time high and are holding back investments in development and climate. While EMDEs should be mobilizing finance to invest in climate and development, they will be paying record amounts to service their debts in 2024.

Figure 1: The composition of the external public debt of EMDEs (with the exception of China) by creditor, 2008-2022 in billions of dollars

Source: Debt Relief Project for Green and Inclusive Recovery, 2024. Data source: Compiled by the authors using World Bank (2023). Note: Includes 123 EMDEs, according to the World Bank's International Debt Statistics coverage. The World Bank Group comprises the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), the International Development Association (IDA), the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). All rights reserved

Exacerbating the economic situation, borrowing on private capital markets is out of reach for most EMDEs. Due to bond yields that exceed expected growth rates (see Figure 2 for a selected sample of countries), EMDEs cannot rely on capital markets to refinance or seek new loans without jeopardizing their debt sustainability. Although EMDEs do not borrow solely from bond markets and it is important to alleviate a measurable cost of credit, bond markets have become an increasingly important source of financing for EMDEs, pushing up the overall cost of capital. This situation indicates that debt suspension efforts, especially in periods of high interest rates, need to be deployed carefully to avoid exacerbating debt loads and are not an efficient substitute for debt relief.

Figure 2: Selected countries - Sovereign bond spreads (change between January 2023 - January 2024), borrowing costs and projected nominal GDP growth.

This situation highlights a worrying pattern for EMDEs, where external constraints are compounded by debt loads. In addition to macroeconomic shocks - such as monetary tightening in advanced economies - EMDEs are also relatively more exposed to climatic shocks, such as hurricanes or floods. These physical events devastate critical infrastructure, leading to capital flight, falling exchange rates and high credit costs. As shown in Figure 3, this situation can lead to a vicious cycle, in which vulnerability to climate change and its associated economic and fiscal shocks impede governments' ability to build climate resilience.

Figure 3: The impacts of fiscal and monetary policies on climate change

Creating an extended DSA

Despite the debt-related challenges faced by EMDEs, the international community does not have adequate tools to assess which countries need debt relief and how much. The IMF conducts its own DSAs to identify a given member state's vulnerability to sovereign debt difficulties and the level of debt relief needed to restore its debt sustainability. However, the IMF's DSA was flawed in many respects, including biased projections, unrealistic climate investment needs and underestimating the impacts of climate shocks.

The IMF and World Bank's Low Income Country Debt Sustainability Framework (LIC DSF) is currently under reform, creating a crucial opportunity to include realistic assumptions of climate and development financing needs.

In our expanded DSA, we account for external financing needs for development and climate change according to the recommended levels estimated by the G20 Group of Independent Experts.

The expanded DSA focuses on 66 of 73 economically vulnerable countries included in the LIC DSF, excluding seven countries due to data constraints. The 47 EMDEs identified as being at risk of facing insolvency problems in the next five years in seeking to build investments to meet climate and development goals are marked in blue in Figure 4. We refer to these 47 EMDEs as the "New Common Framework Countries" (NCF), indicating that they should receive urgent attention under the Group of 20 (G20) Common Framework, the key forum for debt restructuring. Most of these EMDEs are in Africa and include economies such as Mozambique, Kenya and Côte d'Ivoire, among others.

In addition, we have identified 19 EMDEs that lack liquidity and fiscal space for investment in climate and development and will not be able to finance the necessary investments without credit enhancement or liquidity support. The 19 EMDEs are shown in green in Figure 4 and encompass diverse economies such as Mongolia, Rwanda and Bangladesh, among others.

Figure 4: Result of the external debt sustainability analysis: Countries in need of debt relief

Sharing the burden of debt relief

In 2022, the 47 countries identified in the report owed 383 billion dollars in nominal debts (including IMF credits), which, as Figure 5 shows, are mostly owed to multilateral creditors (91.5 billion to the World Bank and 57.6 billion to other multilateral creditors), followed by private creditors (59.6 billion to other bondholders and 40.3 billion to other private creditors), China (55.1 billion), the Paris Club (28.9 billion), the IMF (24.9 billion) and other official bilateral creditors (24.5 billion). This diverse panorama of creditors highlights the need for all classes of creditors to participate in debt relief efforts.

Figure 5: NCF (47): Nominal debt stock by creditor group, 2022, in billions of dollars

However, the division of burdens between classes of creditors has been a controversial issue and has led to delays in negotiation. To optimize the efficiency and effectiveness of sovereign debt restructuring, it is essential to have a clear and transparent approach to equally dividing the burden among creditors. Building on our previous DRGR Project research, the report suggests adopting a "fair" Comparability of Treatment (CoT) rule to account for the distribution of losses depending on the concession rates of the debt incurred. In short, creditors that charge lower interest rates "ex-ante", such as multilateral development banks (MDBs), will be responsible for a smaller proportion of losses, while those that price default risk "ex-ante" should bear greater losses in the event of default.

Despite charging for default risks, bondholders have not absorbed proportional losses in cases of debt relief. As recent negotiations with bondholders under the Common Framework - such as Suriname and Zambia - show, the high remuneration of bondholders is hardly touched even after debt negotiation, while countries in debt difficulties are left with high debt service obligations that can impede their economic development. It is critical that bondholders participate adequately in debt relief efforts, and for this to happen, adequate legislative provisions in key jurisdictions - such as New York - must be combined with incentives for bondholder participation in debt relief - such as a revised Brady Bond proposal.

Bondholders are not the only class of creditors that need to be more involved in debt relief. Although MDBs often provide high levels of concessionality, for many countries identified as in need of debt relief, achieving debt sustainability hinges on including MDB demands in debt restructuring negotiations. Figure 6 shows that at least 16 EMDEs that are in need of debt relief will pay more than half of their debt service to MDBs over the next five years. It is essential that MDBs participate in debt relief negotiations, albeit in a way that does not damage their credit ratings.

Figure 6: Average debt service (2023-2030) to multilateral creditors as part of sovereign external debt service.

Debt relief for green and inclusive recovery

To achieve a fair and efficient debt relief process, the DRGR Project has developed a proposal for coordinated and comprehensive debt relief to free up resources in EMDEs with heavy debts to promote a just transition to a low-carbon, socially inclusive and resilient economy. The DRGR Project proposal rests on three pillars, as shown in Figure 7.

The first pillar establishes that public and multilateral creditors must guarantee significant debt reductions that not only return a struggling country to debt sustainability, but put the country on a path to meeting development and climate goals - in a way that preserves the financial health and credit rating of multilateral institutions.

Under the second pillar, private and commercial creditors secure reductions in debt commensurated by public creditors with a "fair" CoT. These creditors need to be compelled to enter into negotiations through a combination of reward and punishment incentives.

Finally, under the third pillar, credit enhancement should be provided to countries that are not in debt distress but lack the fiscal space to reduce the cost of capital, alongside other forms of support such as temporary suspension of debt servicing to ensure countries' liquidity by increasing fiscal space to invest in a green and inclusive recovery.

Figure 7: Three pillars of debt relief for green and inclusive recovery

Policy recommendations

The report's findings highlight the need for urgent reform in three main areas.

First, DSAs, which are under review at the IMF, need to be increased and calibrated to account for the critical development and climate investment needs of EMDEs, as well as the potential for climate change and other shocks.

Second, the G20 Framework needs to be based on expanded DSAs, compel all classes of creditors to participate and deliver a level of debt relief necessary to mobilize financing for climate and development objectives.

Finally, credit extensions and debt service suspension - for example, with a revitalized and expanded Debt Service Suspension Initiative - should be provided to the 19 EMDEs identified as facing liquidity rather than solvency problems and lacking fiscal space for development investments. Here, the temporary suspension of debt service and a new profile should be coupled with new financing in which the measured cost of capital is lower than the projected growth rate of the participating countries.

The future of EMDEs is at a crossroads. If current economic and political trajectories persist, the international community will experience non-compliance with the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, the repercussions of inaction would result in devastating social, economic and environmental costs, which could become irreversible.

However, there is another way.

If countries can accelerate investments in climate and development, the world economy can evolve into one that is low-carbon, more equitable, resilient and conducive to shared prosperity.