Disinformation in the Legal Amazon, especially as Belém hosts the COP30, has been the subject of various recent studies. Reports from the project “Amazônia Livre de Fake” INTERVOZES, 2023; 2024) identify three central segments of local dissemination: right-wing organizations and activists, political figures, and journalistic outlets. Many of these actors have ties to agribusiness and employ their own means of communication to spread content allied with their interests, in which setting 48% of Brazilian municipalities are “news deserts”—cities or regions that have no local journalism and which today represent five out of ten Brazilian towns (PROJOR; VOLT DATA LAB, 2023), the northern region having the lowest density of local outlets.

According to Intervozes (2023), disinformation is not simply truth vs. lies, but is a deliberate strategy of constructing a view of the world based on a developmentalist and predatory model, contrary to the rights of indigenous and traditional communities. This analysis mirrors the observations of the Democracy in Check Institute, which describes socioenvironmental disinformation as a systemic phenomenon, sent out in narrative waves according to the interests of its disseminators.

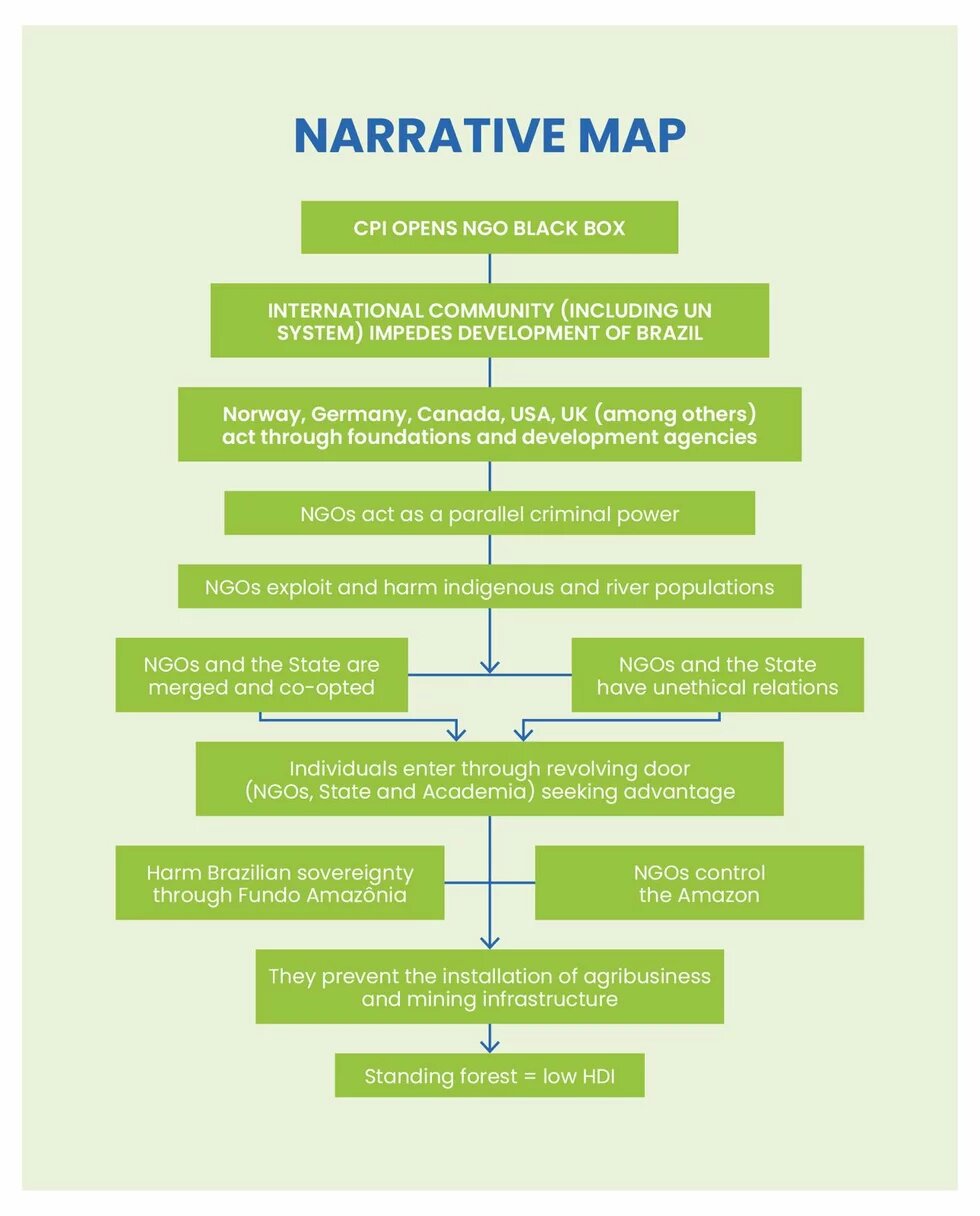

A striking example occurred at the CPI das ONGs (Parliamentary Inquiry Commission of NGOs) held by the Federal Senate in 2023 and led by members of parliament from the north of the country, including Plínio Valério (PSDB-AM) and Márcio Bittar (União-AC). The commission became a stage for climate-change denial and attacking socioenvironmental organizations, with claims that the international community—including the UN—sought to impede the development of Brazil (FRANCO et al., 2024). This rhetoric of “constrained progress” contrasts with the perception of the regional population: the “Pesquisa de Valores Ambientais e Atitudes sobre a Amazônia,” or, “Study of Environmental Attitudes and Values Regarding the Amazon”(UFPA, 2024) shows ample adherence to environmental policies and high (53.7%) confidence in the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (Ibama), indicating positive receptiveness to socioenvironmental protection agendas.

1. Typologies of disinformation narratives related to climate and environment

Disinformation posts about the Amazon focus on criminalizing NGOs and environmentalists, and glorifying the military as supposed defenders of the region (INTERVOZES, 2024). This idea was reinforced during Jair Bolsonaro’s presidency, which promoted extensive militarization of socioenvironmental management agencies. Seibt (2020) identified 99 military personnel in leadership roles within these institutions, including 19 in Ibama and 17 in ICMBio; by the period's end, only two of Funai's 39 regional coordinations were headed by career civil servants (INFOAMAZONIA, 2023).

The mapping of the most frequently recurring narratives reveals four main themes:

- “External Interference” or “Loss of Sovereignty,” associating deforestation control policies with international meddling.

- "Stifling of Development," alleging that governmental actions hinder economic progress.

- "Enclosure of the Amazon," accusing environmental policies of restricting national sovereignty.

- Attacks on environmental managers and agencies, especially MMA, ICMBio and Ibama, often accompanied by misogynistic offenses against Minister Marina Silva. These narrative attacks support a legislative agenda aimed at easing environmental protection and weakening oversight power of these agencies. Recent examples include PL 2159/2021, which aims to relax environmental licensing under justification that control agencies are “slow” and “stifle development”; approval of the Temporal Framework Law (Law 14.701/2023); proposals to regularize invaded lands such as PL 2633/2020 (the "Grilagem" or “land fraud” bill); and projects permitting mining on Indigenous lands (PL 191/2020).

2. Coordinated Disinformation on Climate and Environment

Climate and environmental disinformation forms part of coordinated political communication structures, amplified by right-wing and far-right actors frequently linked to agribusiness, mining, or control of media and means of communication. This is an organized informational ecology in which ideologically driven content is produced, disseminated, amplified, and monetized interdependently.

Digital platforms—especially X (formerly Twitter), Telegram, and WhatsApp—function as engagement infrastructures favoring divisive messages, promoting polarization, and mobilizing emotions and symbols. Their recommendation algorithms, optimized for emotional reaction metrics, amplify discourses based on ambiguity, fear, distrust, and nationalism, making narratives on “loss of sovereignty,” “stifled development,” and attacks on environmental agencies notably effective in the digital environment.

This system appears in moments of crisis, when disinformation acts as a mechanism to politically frame disasters. For example, during the 2024 floods in Rio Grande do Sul, right-wing networks mobilized content blaming environmental legislation, attacking NGOs and scientific institutions, and downplaying the climate causes of the tragedy, as mapped by Capone et al. (2024). A similar pattern was observed in the Amazon in 2019, when volunteer firefighters were arrested in Alter do Chão, in the state of Pará, who were falsely accused of starting the very fires they fought. The tactic was repeated during the severe drought and fires in the Amazon in August 2024, when monitoring by the Democracy in Check Institute identified opposition politicians, including Flávio Bolsonaro and Damares Alves, who exploited the crisis to question the federal government and Minister Marina Silva, spreading narratives that artists and environmentalists had conveniently gone silent. These episodes illustrate a recurring pattern already seen during the CPI das ONGs, where similar notions were systematically spread to undermine the legitimacy of science and environmental public policies. Recent surveys indicate that the reach of posts aimed at undermining Brazil’s credibility as the COP30 host more than doubled on social networks, reaching 1.2 million users in August, compared to the average of 486,000 from January to July.

In both cases, a cyclical socioenvironmental disinformation system is observed, where narratives are reactivated depending on the political context, adjusted for power disputes and specific economic interests. This dynamic reinforces predatory developmentalist views, erodes social trust in institutions, and compromises the formulation and effectiveness of climate mitigation and adaptation policies.

Conclusion

Disinformation in northern Brazil is part of a coordinated system of political communication, sustained by economic and ideological interests that shape public perceptions of science, the environment, and the State. More than merely spreading falsehoods, these networks construct propagandistic frames of symbolic manipulation that legitimize a predatory model of development and erode trust in institutions. This system is particularly effective in a context of deep digital inequality: the northern region has the lowest connectivity rates in the country, with states such as Acre, Amazonas, and Pará ranking last in household internet access (SALDANHA, 2024). This precarious infrastructure, where access depends almost exclusively on mobile phones, limits the consumption of more complex media and reinforces the use of instant messaging applications—which are already the most common online activity in Brazil (CETIC.BR, 2023). This dependence on apps such as WhatsApp, combined with the scarcity of local journalism (PROJOR; VOLT DATA LAB, 2023), creates an ideal environment for the circulation of disinformation within closed networks, composing a political structure of manipulation.

The articulated action of political, media, and business actors, empowered by digital platforms, turns themes such as sovereignty and progress into anti-science and anti-environmental discourses, forming a genuine political grammar of disinformation. This dynamic reinforces communication inequalities and increases democratic vulnerability in the Amazon.

Confronting this phenomenon requires public policies aimed at informational integrity, focusing on local journalism, algorithmic transparency, and media and scientific literacy. Such measures, integrated among the State, universities, and civil society, are essential to strengthen democratic resilience and protect biomes and collective rights in the face of new forms of digital manipulation.

However, the strengthening of these pillars faces significant barriers in the Amazonian context. Local journalism, essential for fact-checking in the territory, suffers from economic precariousness and operates in news deserts, where the northern region has the lowest density of media outlets in the country. Moreover, communicators investigating socioenvironmental crime often face harassment and threats from those linked to mineral and agribusiness interests. Algorithmic transparency collides with the business model of digital platforms, which are optimized by emotional reaction metrics and profit by amplifying narratives of fear and distrust.

Overcoming these challenges is crucial, as climate denialism is not merely an opinion but a strategic device that generates inaction and serves as a direct barrier to climate change mitigation and adaptation. This disinformation, often tied to interests seeking to delegitimize environmental policies, poses a central threat to biome protection.

Recognition of this challenge is shifting the global approach. Preparations for COP30, to be held in Belém, are innovative in placing Information Integrity on Climate Change as a pillar for successful climate action. This new perspective focuses not only on combating disinformation but also on proactively promoting a healthy information ecosystem. Concrete examples of this effort include the Global Initiative for Information Integrity on Climate Change—launched by Brazil, the UN, and UNESCO at the G20—and the articulation of the Network of Partners for Information Integrity on Climate Change (RPIIC), which brings together more than 120 Brazilian organizations, coordinated by the Democracy In Check Institute as secretariat. These efforts represent a fundamental step for collaboration and science to overcome denialism, protecting both democratic resilience and the future of the climate.

References

CAPONE, L. et al. Narrativa e desinformação no contexto da crise climática do Rio Grande do Sul #1. Instituto Democracia em Xeque, 2024. Available at: https://institutodx.org/publicacoes/narrativas-e-desinformacao-no-conte…. Accessed on Oct. 7, 2024.

CETIC.br. Pesquisa TIC Domicílios 2023: resumo executivo. São Paulo: NIC.br, Aug. 2024. Available at: https://cetic.br/media/docs/publicacoes/2/20240826110955/resumo_executi…. Accessed on: Oct. 20, 2025.

FRANCO, A. de O. et al. Inventário das sessões da CPI das ONGs. Instituto Democracia em Xeque, 2024. Available at: https://institutodx.org/blog/relatorios-de-monitoramento-da-cpi-das-ong…. Accessed on: Oct. 7, 2025.

INFOAMAZONIA. Funai inicia “desmilitarização” após quatro anos de governo Bolsonaro. InfoAmazonia, Jan 19, 2023. Available at: https://infoamazonia.org/2023/01/19/funai-inicia-desmilitarizacao-do-qu…. Accessed on Oct. 20, 2025.

INTERVOZES – Coletivo Brasil de Comunicação Social. Combate à desinformação sobre a Amazônia Legal e seus defensores. 2023. Available at: https://amazonialivredefake.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/INTERRelator…. Accessed on: Oct. 7, 2025.

INTERVOZES – Coletivo Brasil de Comunicação Social. Combate à desinformação sobre a Amazônia Legal e seus defensores. 2024. Available at: https://amazonialivredefake.intervozes.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2024/0…. Accessed on: Oct. 7, 2025.

PROJOR; VOLT DATA LAB. Atlas da Notícia. São Paulo, 2023. Available at: https://www.atlasdanoticia.jor.br/. Accessed on: Oct. 7, 2025.

SALDANHA, R. Mais de 20 milhões de brasileiros não têm internet em casa, diz IBGE. CNN Brasil, Dec. 12, 2024. Available at: https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/nacional/mais-de-20-milhoes-de-brasileiros…. Accessed on: Oct. 20, 2025.

SEIBT, T. Governo Bolsonaro tem 99 militares comissionados na gestão socioambiental. Fiquem Sabendo, Oct. 22, 2020. Available at: https://fiquemsabendo.com.br/meio-ambiente/militares-gestao-socioambien…. Accessed on: Oct. 20, 2025

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARÁ – UFPA. Pesquisa de valores ambientais e atitudes sobre a Amazônia. 2024. Available at: https://ppgcp.propesp.ufpa.br/index.php/br/programa/noticias/todas/484-…. Accessed on: Oct. 7, 2025.

This article was published in "Democracy under pressure: reflections on the far right with keys to the past, present and future."