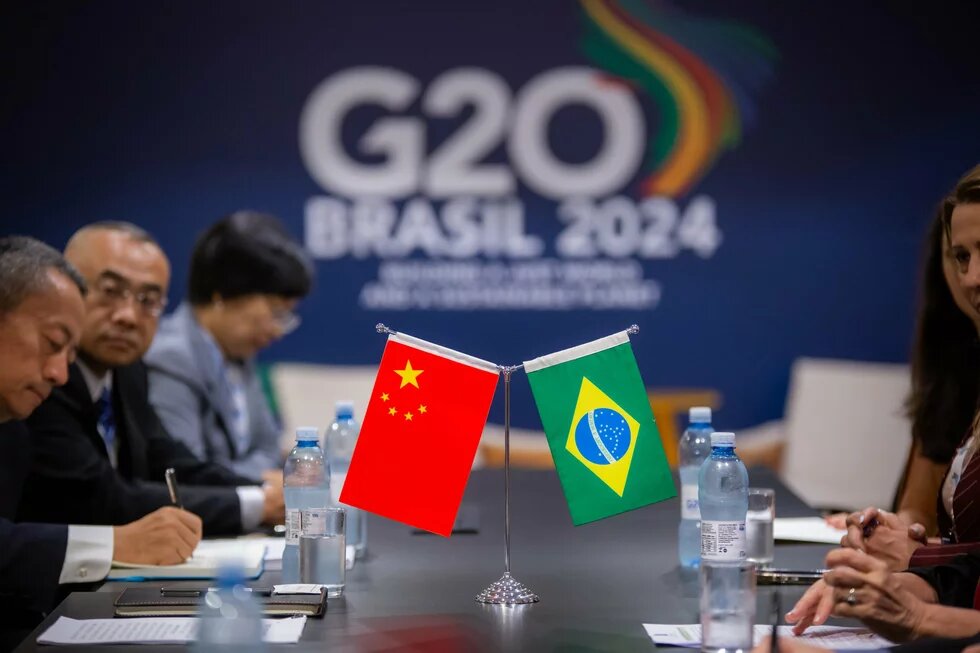

Chinese President Xi Jinping is currently in Brazil for the G20 Summit, following his participation in the APEC Economic Leaders' Meeting in Peru from November 13 to 17. His presence at these two key forums in Latin America highlights Beijing’s growing focus on the region, which already includes 21 nations under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Xi’s back-to-back engagements in Latin America signal China's strategic priorities and deepening ties with this part of the world.

At the same time as the Chinese leader has been betting on multilateral concertation spaces such as APEC and the G20 to foster regional and global economic cooperation, he has been using these meetings to advance the New Silk Road, patiently stitched together over the last 10 years through bilateral agreements signed with more than 150 countries. One of the examples of this global infrastructure network will be shown by Xi during his stay in Peru, when he will take part in the inauguration of the first Chinese port in South America, the Chancay megaport, north of Lima. Largely financed by China's state-owned COSCO Shipping Ports, the port promises to make it cheaper to export goods from Latin America, including Brazil, to the Asian market by considerably reducing logistics costs and transportation times for trade between the regions. This is the business card that the Chinese leader intends to take to Brazil during the G20.

The environmental and social contradictions of the project, as well as the asymmetrical nature of the trade that will be facilitated by the new port, which is characterized by exports concentrated on primary products from Latin American countries, which are increasingly coveted as the home of critical minerals essential for the energy transition, and imports of high value-added products from China, are invisible. On the other hand, it must also be considered that the geo-economic dispute between the United States and China has an impact on Latin America, especially since Trump's victory in the last US elections. Given that Trump has already anticipated implementing an even more aggressive trade policy towards China than in his first term, with the imposition of tariffs of 60% on imports of Chinese products, China will need to rely more and more on its Latin American partners.

Faced with this scenario, Brazil has chosen to distance itself from this geopolitical crossroads and not give in to a more rigid alignment with either the United States or China, maintaining its autonomy and voice in world affairs. Ambassador Katherine Tai's comment that the Brazilian government should weigh up the risks of joining the New Silk Road was read as irresponsible by the Chinese Embassy in Brazil. Meanwhile, Brazil has been sidestepping both sides and trying to prevent the United States from defining its interests and dictating the direction of its foreign policy. Even though it lacks in terms of infrastructure, Brazil has chosen not to formally join the New Silk Road, not clinging to labels, as defended by the President's international affairs advisor, Celso Amorim.

One of Brazil's bets has been to change the profile of trade relations with China, which today is centered on the export of agricultural and mineral commodities, above all soybeans, but also iron ore, oil and meat, in order to reverse the country's deindustrialization process. Brazil therefore insists on the need for China to transfer technology, invest in research and innovation and in the industrial sector. With this in mind, Brazil believes that any trade and investment agreement should be customized, aimed at improving the content of trade between Brazil and China. In fact, one of the aspects highlighted by China itself in its modernization process is the idea that this process must respect the material conditions, historical and social contexts particular to each state, as opposed to the idea of predefined development routes.

Since 2009, China has become Brazil's main trading partner, overtaking the United States. However, to understand Sino-Brazilian relations, we need to go beyond bilateral trade relations and delve into the political universe of global governance. In the G20, Brazil and China have shared objectives that are reflected in other multilateral forums, such as the BRICS. It's important to note that, with the growing paralysis of the United Nations (UN), the global governance system is becoming increasingly decentralized, but this doesn't mean that the different groupings operate in isolation, since discussions in the BRICS, for example, spill over into the G20 and vice versa.

The shared objectives between China and Brazil can partly be deduced from reading the Declaration of the BRICS Summit in Kasan, Russia, in October of this year. Both countries advocate a multipolar order, without the dominance of a single power, a more equitable system of global governance, the reform of the international financial architecture to make it more representative of the countries of the Global South and advocate that ongoing geopolitical disputes should be resolved within the multilateral framework of the UN. The document signals the recognition of the G20 as the main global forum for multilateral economic and financial cooperation and draws attention to the window of opportunity opened up by the fact that the last G20 troika will be made up of countries from the Global South and, more specifically, the BRICS: Brazil (currently in the presidency), India (2023) and South Africa (2025).

In its presidency of the G20, Brazil has given centrality to tackling global inequalities, an agenda dear to China's heart. This inequality, which is structural to the liberal international order, is expressed in the international institutions established after the Second World War, such as the UN Security Council and the Bretton Woods Institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB). Both countries have insisted on reforming global governance to give more voice and representation to the countries of the “Global South”.

Inequality, which structures international relations, can only be overcome, in the Brazilian government's view, through redistributive policies that allow capital flows to take the opposite path to colonization. According to Lula, what we are witnessing today is a “Marshall Plan in reverse”, a dynamic that deepens inequalities as poor countries continue to finance richer ones. It is in this spirit that Brazil has proposed tackling global tax inequality by, for example, taxing the super-rich, which could fund public policies aimed at fighting hunger, poverty and the climate crisis, among others.

It is predicted that this tax could create a fund of between 200 and 250 billion dollars a year, part of which could be directed towards the Brazilian government's innovative initiative to create a Global Alliance against Hunger and Poverty, which aims to mobilize a network of countries and organizations to exchange knowledge and successful experiences in the fight against hunger. Brazil, with its history of reducing hunger through policies such as Zero Hunger and Bolsa Família, has a wealth of experience to share. China has already publicly joined the Alliance and can provide valuable lessons in the fight against hunger, as it has practically eradicated food insecurity in recent decades by investing in rural infrastructure, research and technology. Both countries propose a path centered on solidarity, the exchange of knowledge and financial cooperation to eradicate hunger and poverty in the world.

Trump's election promises to further intensify the ongoing trend in both Washington and Beijing of decoupling the US and Chinese economies. In addition, climate denialism, the US's expected withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and the tendency to reduce rather than increase taxation on the super-rich not only run counter to Brazil’s and, to some degree, also China's priorities in the G20 and BRICS, but also have the potential to erect new walls, hatreds and disconnections around the world. Perhaps this confrontational strategy of the new US administration might become a stress test for the resilience of the newer global governance instruments, namely, G20 and BRICS.